HS: When I first reached out to you I found a story on your site where you had traveled somewhere and that experience got you into death, but I couldn’t find it when I looked on your website again.

AA: Yeah, I took it down.

HS: I’m just curious, what’s the story. How did you become interested in death?

AA: I had been practicing law for 10 years and found myself really unhappy and burnt out. I was working at legal aid so I wasn’t doing high priced fancy law. I was working with the people, serving down in the trenches. I burnt out. Then there were budget cuts at work and then I got moved into this place that I call affectionately, “the dungeon.” This was not a very happy place. It was miserable, no light, concrete upon concrete. I would drive into a concrete parking structure in the morning, walk into like a concrete corridor, and into a concrete office with no windows. The mild grade depression I was feeling just ballooned and became this big heavy cloud of darkness, so I took a medical leave of absence.

I went to a friend’s house in Colorado. While I was there I started meditating daily again. I had regularly meditated in times prior but really I committed to it this time because I didn’t know what else to do to get myself back to the joyful, colorful, human that I had known. One morning I went to the library and a book literally jumped off of the shelf and landed at my feet. It was Anita Moorjani’s, “Dying to Be Me.” It was about a woman who had a near-death experience after a four-year dance with cancer. What she learned was really familiar and relatable and yet her experience was filled with things I knew nothing about.

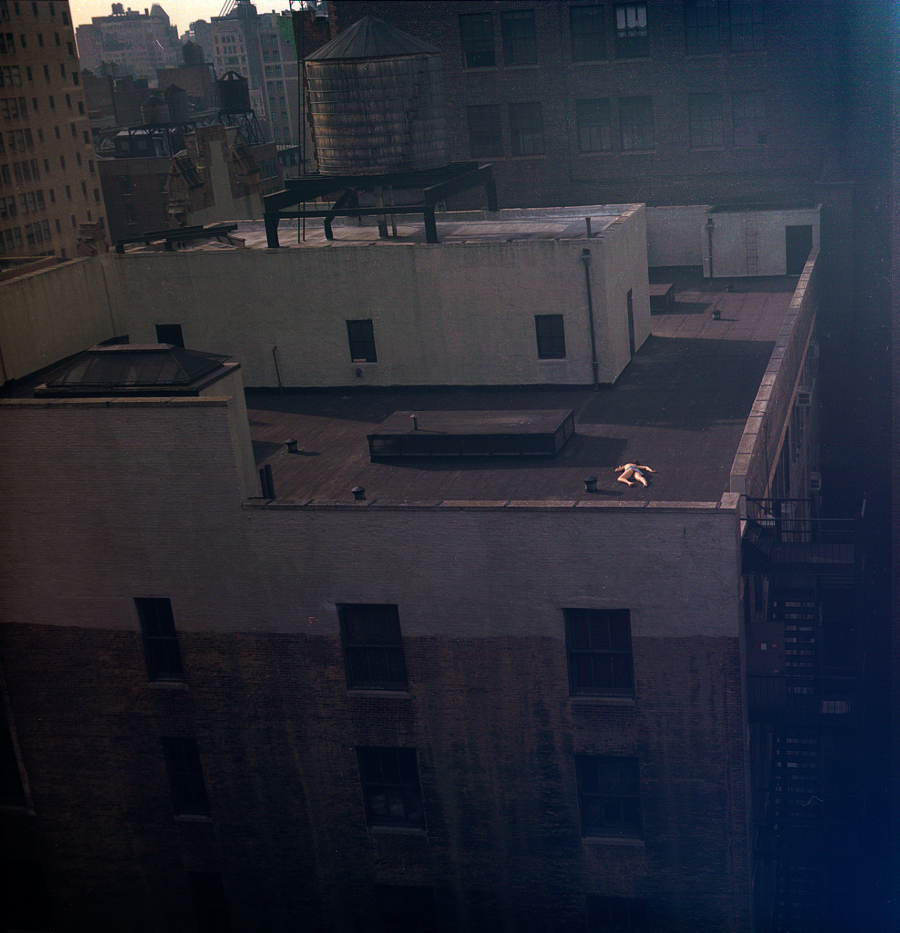

I finished the book and was getting ready to return it when Elian Gonzalez popped into my mind. I don’t know if you know or remember him, but he was this kid in the ’90s who had come over on a raft from Cuba with his mother. In the last part of the trip she died, but he made it to land safely. He was six. There was an image stuck in my head of when the U.S. found him. They had been trying to send him back to Cuba, but his family members had been hiding him in Miami. It was a very stark image. His uncle holding him in the closet and sheer terror on Elian’s face. I started thinking about that kid and whatever happened to him after they sent him back to Cuba. I wonder who he lived with. Cuba was on my mind.

When I went back to the library that afternoon to return the book and I found a Greenpeace worker. He went to his bag to get me a pamphlet and on his bag it said, “Cuba Te Espera,” which means, “Cuba Awaits.” It turns out that that was the tourism company for Cuba back in the day. I don’t really believe in coincidence, so I decided I was definitely going to Cuba.

I bought a ticket, went, and spent a couple weeks traveling by myself. I got that spark of joy again. I was so excited that it was coming back and not gone forever after the depression. Later, I was in a town called Trinidad and I met a woman on a run one morning. She decided she wanted me to go out with her, so she could find me a boyfriend. She put my hair up in this scrunchy to make me cute for the guy that was going to be my Cuban boyfriend, which he wasn’t at all. He was so young and he didn’t speak a word of English. It was nothing romantic, but we had a lot of fun. We were in a limestone cave in the middle of a mountain, which was super cool. It was also kind of strange because there were all of these Europeans there who thought I was a Cuban prostitute. That’s a whole other story.

Anyway, in the morning I woke up really late, hungover, and went to go return the scrunchy to the women. In Cuba, there is a high value on things because they don’t get very many new things in the country, so I went to go take the scrunchy to her. Along the way a car almost hit me. I put my hands on the car and I was like, “Oh my gosh, get it together. Don’t die on this street here.” I gave her the scrunchy made it back to by the bus stop in time.

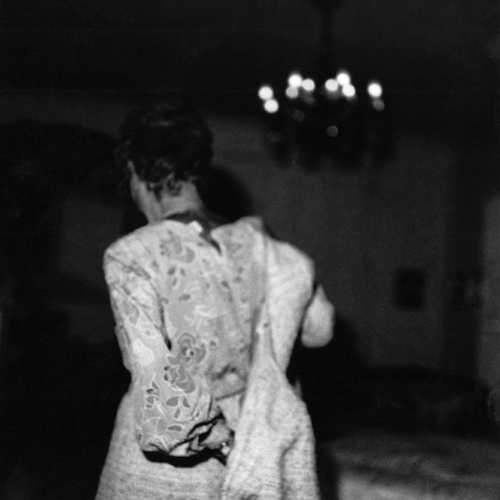

At the bus stop I met a young woman who offered to save my place in line while I got tickets because I was late. She was going to stall the bus so I could get on it, which she did very well, in a silly way. She was being completely ridiculous and I was watching her thinking, “She’s really willing to make a fool out of herself.” We started laughing hysterically about how of control and way over the top she was. It was hilarious and it was super cute. Needless to say, we were instant friends. We got the last two seats on the bus and started talking over the woman who was in between us. Before long we started getting deep. She told me that she had uterine cancer and was on a trip to see the top places she wanted to see before she died, Cuba was amongst them. She was really scared to die. The cancer diagnosis had brought her mortality into the full view and she was terrified of death.

Through our conversation, it became clear to me that her desire to travel came more from the fear of death rather than embracing life. You know very different vibrations. One is like, “Oh no, I’m going to die.” The other is like, “Well shoot, I’m alive now. What am I going to do with it?”

We talked a lot about death. I lead her through meditations on death. I don’t know where I was pulling this stuff out of, but we had a really beautiful time on the bus. We talked about her passions, her life, what it was she felt she hadn’t yet done, what she wanted to do with her life, and so on, and so forth. We spent seven hours on the bus together. When we got to her stop and she was supposed to get off she decided to stay with me, which was really beautiful. We laughed and coveted our neighbor’s ice cream and watched music videos from the ’80s on the bus. It was a really magical time.

On that bus ride, I got super clear that I was going to work with people who were dying. I was really sad that she had never spoken to anyone about her fear of death before. Here I was a perfect stranger and she’d opened up to me. It seemed to be a really good and positive experience. I was on leave of absence from my legal career, but I didn’t know that I wasn’t going back. I felt strongly that I was going to work with people that were dying.

We went to my place in Santiago de Cuba and had a really beautiful evening. We were in bed when she said to me, “Remember when you were in Trinidad?” — the city that we had left fourteen hours prior.

I said, “Yes”

She said, “You were running through the streets, right?”

I was like, “Yeah,” but I was thinking, “Why does she know that?”

She said, “A car almost hit you.”

I said, “Yeah.”

She was in that car that almost hit me in the street on Cuba — so trippy. It was literally a collision into what my life’s work would be.

This set me on a course, but also set her on a course. The reason we started talking at the bus stop was because she had a tattoo of a quill pen on her arm. When I asked her about writing, she said that she just liked it. However, when we were talking about her life, what she regretted was about writing. That was really her passion. I wanted to know, “Why aren’t you writing?” She turned her six-month trip into a book which became a bestseller in Germany. She’s now a published and decorated author. Our meeting really set us both on brand new courses in our lives. I am eternally grateful for her. She’s a soul sister like none other. We’re still in touch. She’s totally healthy, cancer’s in remission, writing, living, loving. It’s beautiful.

That’s the story of how I fell into death work. It’s been a long wild road.

I had to figure out what I was going to do with people who are dying? I applied to psychology programs on death and spirituality. I got into a couple of them, but I wasn’t quite sure. I met this great German guy, fell in love with him, and spent a couple of years traveling around the planet with him. I still wasn’t sure that I wanted to do the Ph.D. route. Somewhere along the line I found death midwifery and kept studying that while being abroad. I would fly back and do classes. Death midwifery seemed like a really good fit, but after spending some time with it, it didn’t quite touch on all of my desires.

The most poignant of these desires was brought to light when my brother-in-law got ill in May 2013. By December he was dead. When he got his terminal diagnosis, I packed up and went to New York where he and my sister and my four-year-old niece were. I essentially midwifed him without knowing that was what I was doing. There was a lot of frustration during that time. There were so many things happening with his body, and there were medical people to explain those things. There were social workers that would check in. There was a hospital chaplain that would come, pray, and be with us. But there was nobody that would answer the questions. Nobody who’s job felt like it was to be with us through this process. Frankly, I was angry. I thought it was really cruel. I felt like it was big missed step in the system. After he died I spent a couple days with my sister trying to figure out things like how to close his accounts. We’d already planned the funeral out, but how do we wrap up all of the affairs of his life. What are the passwords for his accounts? How do we cancel his driver’s license, cancel social security number, figure out what the death benefits are? Where are the people? Where is the guide to help me do this? Where are the people? So I became the people.

HS: Will you explain more about what death midwifery is and kind of contrast it to hospice framework?

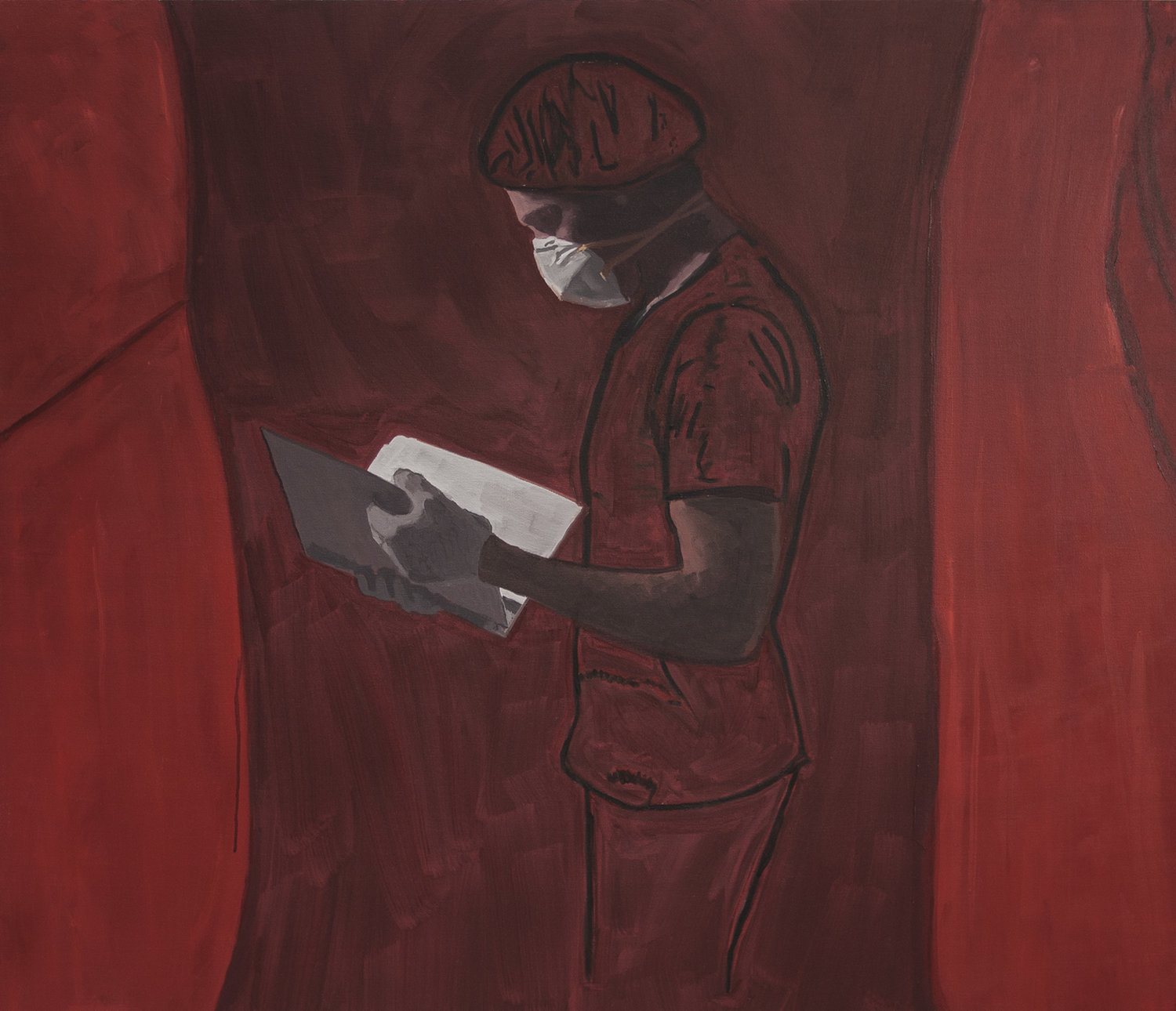

AA: Hospice is a theory of care. It’s based on comfort. It is still medical. It is palliative care so there is medication and making sure that the patient is comfortable. Death midwifery is more of a companion, someone who sits and answers questions, who does all the non-medical care and support of the dying person. Death midwives also help families bathe the bodies, create ritual around the death, can help keep the body at home for vigil-ing. If the family would like, death midwives can also do a home funeral before the body goes off to a crematory or to be buried.

HS: That’s really interesting because most of the exploration I’ve done, people in the death industry are either on the life side of death or on the death side of death. There are all of these nurses and doctors and spiritual counselors and chaplains and social workers and they work with people until the death. Then there are the morticians, the people who run the cremation machines, people helping with the graves. I guess the bereavement counselor would work with the family on both sides, but there seem to be very few people who work leading up to and after death. It’s interesting that a death midwife will help in both ways.

AA: Yeah and that’s what I feel like is really lacking in the system, somebody bridging the gap.

HS: Definitely seems like there’s this middle ground where people are asking questions like, “Can I keep them at home?” and no one knows.

AA: Nobody knows, death midwives know.

HS: What reactions do you get when you tell people you’re an end of life planner? Any funny ones?

AA: Funny, funniest to me is when I say, “I’m a death midwife” and they’re like, “Oh so you know sign language?,” and I’m like, “Well I learned it in college…” Now I understand the connection but the very first time it happened I went on as though I was a deaf — A-F — midwife. They don’t hear death, they hear deaf, and it’s happened quite a few times. When somebody asks me how I find the deaf people, or if I’m deaf, or if I have a deaf sister, or if I know sign language, then I’m like “no-no-no deaTH, like dying.” That’s kind of funny.

There’s one of three reactions I usually get at a party for instance. The first is people say, “Oh god, that’s so interesting,” and then they’ll leave. They’ll go get another glass of wine or go to the bathroom or go find somebody or something. That’s always fun. The next reaction is that people want to talk about grieving somebody has died and they finally feel comfortable to talk about it with a stranger. That’s actually really awesome. The third is that people are like, “I’ve never heard of that, what does that mean?,” and then before long I’m asking them about whether they want to be buried or cremated and they’re like, “Holy shit! How did we get here at a party?”

HS: “I was just eating hors d’oeuvres, what’s going on now.”

AA: What’s going on, why are we talking about my mortality?

HS: Right, gotta spread the word. There’s this question on the Going With Grace website, “What must I do to be at peace with myself so that I may live presently and die peacefully?” Have you experienced any common answers to this question?

AA: Yeah girl, it’s such a juicy one. The commonalities are typically about wanting to leave this earth with some peace of mind. That answer is the biggest commonality but it varies so much by individual. If I were to ask you what dying peacefully and dying with peace of mind meant for you, what would you say?

HS: For me, it would really be about being authentic and also making sure to live my values — treating people with care and respect, and showing the people who I love how much I care about them, including myself. In a nutshell.

AA: In a nutshell. Sum up your entire life in 10 words or less, GO. One thing that comes up a lot is people wanting to make sure that all of their relationships are healed, that’s really important. Another one is people want to make sure that their affairs are in order, meaning that they’re not going to leave a messy estate for their loved ones. By estate I don’t just mean the will and the finances, I’m also talking about practical things like what to do with the body, their stuff, or how to find where their account passwords are.

Healing relationships, cleaning up the estate, living with authenticity, making choices that are in line with who you are (like what you said) — I think those are the top three. Another is leaving nothing unfinished, truly leaving nothing unfinished. Control and leaving estates nice, clean, and healthy are the largest ones for the older people that I talk to and the people that have experienced death of grandparents. Mostly people in their mid-40s that are starting to think about when their parents are going to die and all of the stuff they’re going to have to deal with. I find that a lot of younger people are more interested in living authentically. People of all ages are concerned with healing relationships.

HS: What’s your answer?

AA: Ay dios mios, did you really just ask me that?

HS: Yep [laughs]

AA: What must I do to be at peace with myself so that I may live presently and die peacefully? For me right now, it’s most important that I do everything within my power to bring awareness of death to this culture — to live my purpose fully. That’s my short answer.

HS: It’s a good one, purpose is a good one.

AA: Yeah, purpose is it for me right now. There’s a burning desire, there’s a call in my life and this is it

HS: Has your end of life planning work, have you had to use it personally, has it helped you through deaths of people that you know?

AA: Not since my brother-in-law, which was at the inception of my end of life planning. Nobody close to me has died since then. The beautiful thing is that people call me for advice on what to do within death situations all the time now which I love. A friend of mine is dating a guy who’s mother recently died and she wants to know how she can be with him during this time. I’m not a grief counselor but I’ve been around a decent amount of death — there are some things that help and other things that don’t. We talk a lot about what to do in different scenarios. For example, she offered to close down his mother’s eBay account but she doesn’t have the death certificate so eBay’s giving her a hard time about it. Well, I got some tricks up my sleeves. I like being able to help, I’m a helper.

HS: Have you ever sat with someone when they died?

AA: Yes. My brother-in-law being the first and I’ll tell you about that. He had been sick and when he got a terminal diagnosis they gave him about two weeks. He lived about six after that. Things that went back and forth and they thought maybe they had done something wrong — maybe there was a little bit more time, maybe it wasn’t as bad as they thought. To me, it was pretty clear, though, that he was dying. I don’t know why I knew, but I knew months prior that he was going to die.

He had gone to the hospital because he had decreasing function and his body was starting to shut down, but there was still so much hope. There was also a lot of regret, a lot of sadness, and a lot of fear. My mother, my sister, his parents and myself were the core team around him at that time because it does take a village also. It really does. We were all at the hospital, spending nights there, and waking up there. He didn’t want to die in a hospital but nobody had said, “Hey he’s dying.” Everybody was telling us to jus try this thing and try this and this. I was like why in the hell is nobody just saying the truth. He was dying and he was getting super close but nobody said anything. I still actually carry some anger for the doctor in that situation. Although I understand that the doctor’s job is to heal and for them to say you’re dying means a failure on their part somehow — even though it doesn’t because that’s what happens with bodies. Nobody said that he was dying and I got frustrated because he died in a hospital.

He fell asleep one Sunday night and I was leaving to go take my niece home, she was four at the time. He was having a hard time speaking but he took the oxygen off and he said a bunch of thank you’s and he said he was tired. I responded, “Okay well then rest, no big thing.” I didn’t realize that those would be the last words that were spoken to him. I took my niece home and I came back to spend the night. He was asleep but it was a different quality of sleep. I don’t know how to describe it. He stayed in that state for about a day and a half. Very early morning about 2 a.m. his mother woke us up, we had only been asleep for an hour, and his breathing had changed dramatically. It was very very clear that he was dying, like actually, you know.

We stood around him and I massaged his feet and gave him as much love as I could to carry him on this journey that he was so clearly already on. I kept reminding myself that it was okay, that his time had come. By reminding myself, I guess I was also sending out visions that it was okay for him to let go finally. He had been in a lot of pain and he was very very ill and it was time. There were moments of waiting, hoping that he’d take another breath, but there was also hoping that he didn’t. When he finally he didn’t it was like, “Oh… fuck. That’s it. He will actually never take another breath.” It was very overwhelming. It was also very beautiful. The greatest gift that anyone has ever offered me is allowing me to be present for their dying.

HS: Why do you say that?

AA: Because it’s such a delicate space. It’s such a vulnerable place. It’s such an intimate space. It’s so profound to witness life leave, to see what the end actually looks like, or what the end of this life, as we know it, looks like. Have you ever seen a baby being born? When a baby is being born you feel like, “Oh my god, life has begun.” When somebody dies it’s like, “Oh my god, life has ended.” No more words to be spoken. They will never create anything else. He’s not making anything. He’s not talking to anybody. He’s not putting his hands on anything again. We’ll have no memories of him from this point forwards. This is it. There is a period on this. Similarly when life begins, before this first breath was taken there was nothing, then there’s a brand new life. When life ends it’s like closed book, but can’t open it again.

HS: A birth is intense so I imagine witnessing a death would also be emotionally trippy. It’s like witnessing the edge of the unknown.

AA: I’ve likened it to walking a human as far as you can go with them before you have to turn around. We take them to a certain spot and then at some point we can’t go any further.

I dreamt about my brother-in-law. It was a vibrant colorful dream. There was a parade going by. There was confetti in the air — moving, floating in the air, not falling. It was like there was no gravity for the confetti. Everything was super sparkly. We came out of the parade and my brother-in-law was like, “What are you doing here?”

I was like, “I don’t know.” I felt like I was not supposed to be there — that it wasn’t for me.

He said, “Well that’s okay you’re exactly where you’re supposed to be.”

I was like, “Okay thanks!”

He said, “Stay for as long as you want, but you can’t stay here forever. You have to go back.”

I was resigned, “I’ll go back.”

He gave me a big ol’ hug and got back on the float he was a part of. He was playing this random trumpet. There was like tinfoil confetti, the type that’s on sparkly paper. That’s what the air was. It was just everywhere. Everybody was bright eyed, sparkly, happy, joyful, ecstatic almost.

When I woke up and I was like, “Oh, that’s so weird.” I talked to my mom about it and she helped me unpack it. I feel like it was more about this work where I walk people as far as I feel like I can go. I can push it, but then I have to come back. I can’t go with them to that sparkly parade place until I go there myself.

HS: But you got a glimpse of it and it sounds amazing. Sparkly parade place! What advice do you have for being with people who are dying?

AA: Remember that whatever the person is experiencing is totally okay and correct. We often have a belief about how things should go, but there’s no place where people do things more differently than in dying. As humans we don’t do anything the same anyways, but when it comes to death and dying everybody approaches it differently. How I feel about how somebody else should feel about their death is irrelevant. This goes back to authenticity. Give them space to experience whatever they’re experiencing without our judgments, feelings, and concerns. If they want more pain medication, more pain medication. If they want less, less. No matter what you think. If you think that they should be accepting and understanding, keep that out of the business. If you think that they should still be fighting… Anything that has a should in it, has no place with the dying. It helps a lot when we do our best to keep our own thoughts about death out of the arena.

Feelings can be challenging because there is some sadness that comes along with death and dying. There is a sense of loss, fear, and discomfort that calls our mortality into question. It’s a rich, rich time for feeling as long as we’re not projecting onto other people, but that’s a challenging exercise.

HS: Yeah, it’s challenging even if you are aware of not projecting the should’s.

AA: Very much so. I come up against it all the time. Before entering a house of somebody that’s dying I check my should’s at the door, like a blank slate. I’m just here to be of support. That means whatever they need is what I provide, not what I think they need.

HS: Sometimes I feel like working around death exacerbates all of these lessons that are really useful to know during life. For example, I think of this when I’m doing one of my part time jobs and all of a sudden a priority changes. I had all of these expectations about what I was going to do, but then it changes. You have to let go of how you think things should go and accept the new situation. It’s like what you were saying, there’s no room for “shoulds.” There are so many lessons to be learned.

AA: Absolutely, I think that our richest lessons come from people who are dying or are in space because while we think we’re learning how to live we’re actually learning how to die. We’re learning how to approach our dying while living.

HS: What do you mean by that, will you expand a little more?

AA: In the example that you just gave, you had something that was not going the way you thought it would go — a priority that you had already decided upon was changed. If we can approach situations like that with surrender, acceptance, and an ease, rather than a fighting and a rallying against it, then this situation becomes practice for the loss we experience around death.

When we receive a diagnosis of some sort or there’s an accident, circumstances change. All the future that I had thought I was going to have, all these things I thought I was going to do are suddenly no more. I have options. I can rally against it. I can fight. I can be angry. I can wish it were different. Or I can say, “This is what it is.” I can work with it as it is rather than trying to rally against it. How do I behave when I lose my keys? How do I behave when I’m stuck in traffic? When things aren’t going my way? When I break up with somebody? All those are losses over and over and over again and death is the “ultimate loss.” Again I’m using air quotes because I don’t quite think of death as loss. Instead, I think of death like a divorce from all of the future, all of the things that we thought were going to happen, that we thought we were going to have.

HS: I love that phrasing, “A divorce from what we thought we were going to have.”

AA: …and from the future, what we thought, what we expected, what we felt we somehow were entitled to. We often have this entitlement to life. We wake up expecting to live. It’s a given somehow. I didn’t wake up this morning like, “Holy shit I’m still alive!” No, I was like, “Okay I’m up, first meditate, pee, blah blah, da da dadada.” I’ve already decided that today is going to be mine when in reality I don’t know that.

HS: So funny! I want to start waking up and be like, “Holy shit I’m alive!” That would be great!

AA: Right? Can you imagine the different sort of energy and excitement you would have if you woke up every day like, “WOOOW, I’m alive! I’m still here!”

HS: That would be awesome, I need to work on this.

AA: Let’s try tomorrow.

HS: Yes definitely. So what age group are you working with most of the time?

AA: They’re all over the place, honestly. Everybody should be planning right now. Do you have a health care directive?

HS: I don’t. I need to have one. I talk about it regularly, I just have to do it. I think part of it is that I need to figure out what I want. Where are my lines in my health care directives? When do I want resuscitation to stop? When do I want to keep going? I don’t yet.

AA: Part of my job is to help people figure that out. I ask tough questions but they help people consider options. For example, if you lost any particular function would life no longer feel like it was worth living? What are those functions? For some people, it’s sight. For some people, it’s being able to care for their own bodily functions. At what point does loss of function make life not worth living anymore? How you want to be cared for and what treatments to you want to be given at the end of your life? When you are physically in pain, how do you prefer to relieve the pain? Do you use medication do you prefer holistic methods? What kind of ambiance do you like at home? Do you prefer the quiet? Do you like noise? Do you want the tv always on? Do you like music? What kind of music? All of these things will inform how to treat you when you’re dying.

HS: All these little preferences add up.

AA: All the little things that you learn about yourself as a unique human play into how you die — how you die well and how you die in a way that honors your life.

HS: That makes a lot of sense. I’ve got to get on my paperwork. What do you think are the main barriers that prevent people from doing their healthcare directives or any of the other living will or anything else?

AA: Either they don’t think they’re going to die, they think they have a lot of time before they die, or they don’t want to think about it at all.

HS: It’s also weird figuring out where and how to document your end-of-life decisions. I know about The Conversation Project and I think that walks you through some of this stuff but I’m not 100% sure. Is this site the official thing? It’s just a whole other world that I haven’t walked through yet.

AA: This is the role of an end of life planner. It can be super overwhelming for people. They hear these things and think, “What is this? What does it mean? What do you mean by this?” People fill out those forms without understanding what they’re choosing and not choosing, which ends up becoming even more of an issue at the end of life. I think it’s really important to talk to somebody, ask questions, and have somebody else ask you questions so that you can get clear on what actually want and need.

When I sit with people I start to pick up on things they say they care about. Themes emerge and those themes are the things that make up their values. They probably can’t see them on their own or haven’t identified them objectively before. I help people get clear on their values and then we put what they want in a document that becomes legally binding when signed and witnessed by two people — at least in the state of California. In other states, you might need a witness or to get it notarized. It varies depending on the state.

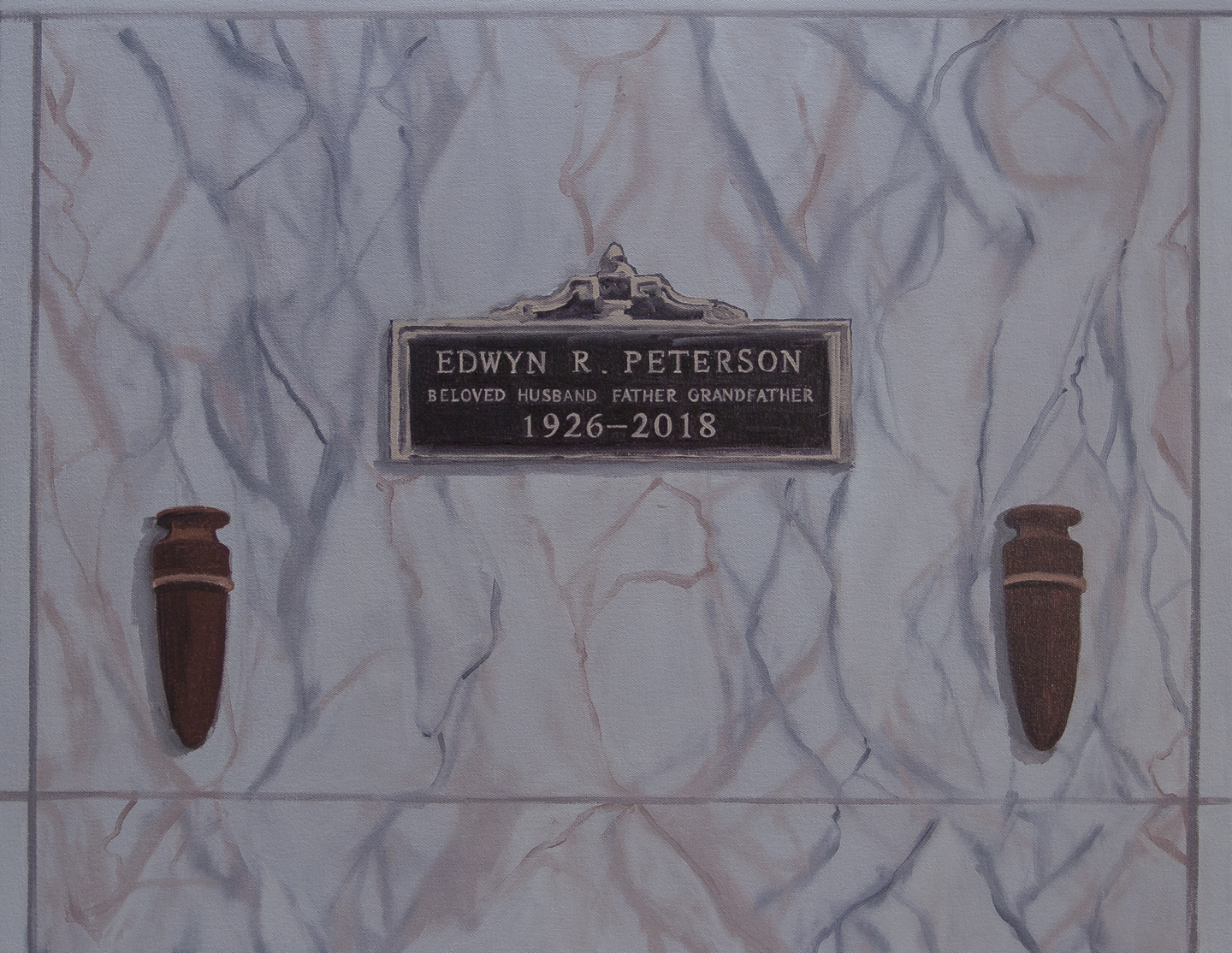

I’ve written advanced healthcare directives that have the healthcare stuff in it but also the death-care stuff in it. In the healthcare portion, you decide on life support and write down how you want to be treated. The death-care portion is where you write down what to do with your possessions, if you have will and where it is, and who your lawyer is. If you don’t have a will, this is the place you write down which things you care about. What should we do with the rest of your stuff? Should we sell it? Should we give it away? Should we give it to dress for success? Should we give it to the archdiocese? What are all your of accounts? What are your passwords? Do you want a legacy setting on your facebook page? should we delete your Instagram account? You probably want to keep yours up — would you want to keep your Instagram account open?

HS: I would want to keep my Instagram account open, my Facebook account can… I don’t care about Facebook.

AA: Okay so delete it or don’t delete it?

HS: Make sure to get all of my photos off of it and then delete it. It’s such a funny thing, I really could care less. As long as someone has the photos I say delete it. Unless someone has some funny project to do with my Facebook account and then they can go for it.*

AA: That’s great to know. There’s also an “in memoriam” setting where you can create a memory page. That way it’s not sending out birthday reminders but people can still post to your wall. Nobody can post on your behalf, but people can gather digitally on facebook to look at photos of you or talk about your life, but it’s not an active page. I ask because the little decisions that we don’t make add up. My brother-in-law is up on facebook in perpetuity and I get reminders of his birthday every year. What are we supposed to do with his profile? My sister is not sure. She feels uncomfortable closing it. His mom says to leave it open. It’s just one example of the very many things about which we say, “Oh it doesn’t matter I’ll be gone anyways.” Well somebody’s going to have to deal with it at some point. There’s three million dead people on facebook, or something crazy.**

HS: Whoa! Facebook zombies, our next Netflix original. It’s crazy, though. I think about death a lot but I don’t think I’ve ever thought about my own social media after I’ve died. I’ve thought about other peoples’. I’ve read articles on funny, different things people have done with their accounts after they have died. We’re nearing the end of our interview, do you have time for one last question?

HS: What do you want your funeral to be like?

AA: Oh girl! It’s going to be a lot of bright colors. I prefer mid to late afternoon outside if possible — weather permitting and it’s a nice enough day. I want it to be outside in nature, trees rather than desert.

I’d like there to be like an actual service inside somewhere because I’d like all of my jewelry to decorate the space. I wear a lot of jewelry in real life. I never have on fewer than forty-one pieces, my ex-boyfriend counted for me. Those are perpetually on my body. That’s just how I go to sleep and wake up so as I move about the day there’s a lot of other jewelry, and I own a lot of it, and people like it and they want it, and I don’t know who to give every piece to because it changes all the time, so my funeral is going to be decorated with my jewelry,

It’s also going to have a lot of really bright colored gilliflowers and daisies everywhere. People are going to dress in color — no black or neutrals really. White is okay, but I don’t want cream, beige, brown, or gray, just color, vibrant color.

I would also like my favorite photos from my travels to be displayed. I’ve traveled quite a bit. There’s a folder on my computer entitled “fav” and the password to my computer is written down in my death-care directive. I’ve written out directions to use these photos, print them off, etc.

It will start mid/late afternoon. There will be the service portion of it, where there will be Rumi poems read. I’ve selected a couple. There will be some songs — maybe my mom’s favorite hymn if she’s still alive. If she’s not, they don’t have to sing it. I don’t care much for hymns. I’d like a funeral procession. I want Little Dragon’s, “Brush the Heat,” to be played because I love that song. The first time I heard it I was like, “Oh my god, please play this at my funeral.” It’s lively and there’s a bunch of clap and snap. It just makes you want to dance. My body will be wrapped in a hot pink and orange shroud. The procession is going to lead to the vehicle where my body will be taken to a green burial site. I can imagine people want to stay there and watch as the vehicle drives off. The people will go back to the dance. I hope at that point that it’s starting to turn into night. I really like dusk, it’s my favorite time of day. I want my funeral to become a party. There is alcohol. There’s music. There’s food. There’re bright colors. There’s dance. There’re twinkle lights everywhere. That is my last party.

I can go to my final resting place and rest in peace, while the loved ones I leave behind can celebrate the fact that I lived and, hopefully, celebrate the fact that I accomplished something while I was alive.

HS: That sounds suspiciously similar to the confetti-parade-land that you experienced in your dream. [laughs]

AA: [laughs] Yeah right, confetti everywhere. I really also want the people who are at my funeral to take pieces of jewelry, put them on, and wear them. That’s how I can get rid of my jewelry without people fighting over it.

HS: That sounds like a good way to do it. Is there anything else you would like to share?

AA: I’d like to explain what my big picture vision is because I think this is important. When everything goes the way that it’s gonna go in my head (you like how that’s a when), everybody that is of age will have a very clear and concise written plan for the end of their lives. This will include how they want to be treated, what their decisions are for life support, what to do with their possessions, what their major accounts are, et cetera. Their funeral directions will be in that plan.

The other part is that there will be somebody to support the family after the death, to help clean up affairs from life. This can be accomplished by having separate centers across the country. I want to have duplicates of me everywhere. I don’t mean me-me, because I think I’m the shit — I mean people who are organized, intellectual, compassionate, kind, and knowledgeable who are there to support families in a rough period of time. It can either be part of the hospice program or an offering from funeral homes. I’d love it if we created this brand new bridge that is the end of life planner.

That’s my big picture vision — that nobody or family deals with death alone.