While creating, "Plaisirs Coupables," Amelie du Petit Thouars faced death when her mother died of cancer and during the Paris terror attacks. In this interview, Amelie discusses how these events affected her creative life and tells us the specific inspiration behind her pieces.

AdPT: HS: When did you start to incorporate death themes into your art and why?

AdPT: I've always been fascinated by this imagery as I've been surrounded by it my whole life. I grew up surrounded by paintings, drawings or sculptures depicting these kind of themes, so it's part of my life! My parents were big Opera fans (lots of drama there) and took me with them to visit the "classic paintings" in Paris or wherever they traveled and to different churches, etc. I didn't understand the significance of these pieces but I knew I was drawn to them very early on.

I've really begun to incorporate death themes when I started this series of drawings, Plaisirs Coupables, back in 2007. Before that, I was in art school and I was stuck with all the assignments we were given. We didn't have much room to really showcase who we were as it was a graphic design course. I started to explore and draw what I liked once I had digested my education and training.

HS: What is your perspective on thinking about death— does it comfort you to think about mortality, or is it disturbing?

AdPT: I'm not really scared of mortality. I grew up catholic (I'm agnostic now) so it's pretty much part of the whole experience of being catholic. Death, the afterlife, etc. I think the thought of our own mortality should drive us in life to accomplish the best and really go for it. It's certainly not disturbing. It's just there. Ultimately, I find that it would be more painful to lose the memories associated with loved ones, than the natural course of death.

HS: Does creating these drawings allow you to confront death or are you creating them for another reason?

AdPT: These drawings have definitely been cathartic for me. They have helped me process different moments in my life that were difficult but not always linked to death. They help me focus and have a hypnotic quality when I make them. My mind goes blank and I forget everything else. It's very soothing but very consuming at the same time. When my mother died of cancer 4 years ago, I felt I really need to finish the series and try to showcase it because I know she would have been proud to see the result. So, it pushed me to finish my work and not disperse myself. I was able to "bury" myself with the time-consuming quality of these drawings.

HS: Have you had any close encounters with death in your life— either near death experiences or people or pets dying? Have they affected your art or how you see the world?

AdPT: I live in Paris, France. On November 13, 2015, we were struck by several acts of terrorism. I was at the EODM concert at the Bataclan with my best friend. We were very fortunate to both get out unharmed but I guess I saw death right here and there. It had a mixed effect on my work: it pushed me to find the energy to create a crowdfunding campaign to print my first fanzine and have my first showcase but I was totally unable to create new pieces. I'm only now starting to have new ideas for drawings again. It's like the creative part of my brain had been shut down for a while, I only saw a wall or a blank page. I'm a graphic designer by trade and going back to work after this was very difficult. We had lost our "juice" and were only able to accomplish repetitive tasks. After a while, it came back but it's been tougher to create new drawings. Right now, I'm trying to work on a book/fanzine to show this process of coming back to a creative life. As for how I see the world, I feel like it's even more absurd than ever and random, but I still want to create stuff and get it out there!

HS: You use supernatural, mythological, and natural symbols of life and death in your work (Chimère, Ouroboros, maggots), what about these symbols are significant to you?

AdPT: I am fascinated by the symbols that men have created to explain the universe or by the magical power they have given to them to protect themselves. I love reading about how these symbols were created and how they've managed to exist throughout the ages and how you can find them in different civilizations.They give you a key to understanding the history of humanity in a magical way. I used to have a dictionary of greek myths when I was a kid and would read it over and over again. Now I'm obsessed with alchemy. It's incredible because it's connected to so many things: history, science, religion, mysticism, biology, etc. I love incorporating and playing with these symbols to create something magical and almost mysterious.

HS: What is your process for composing a particular death-related piece? Is it organic? Are you regularly thinking about these themes? Something else?

AdPT: I always start with an image or a dream that comes to my mind. It comes up and I play with it. It's very hazy, I can't quite explain it. Usually, it comes quite quickly. If I have to sketch too much I find that it won't end up working.

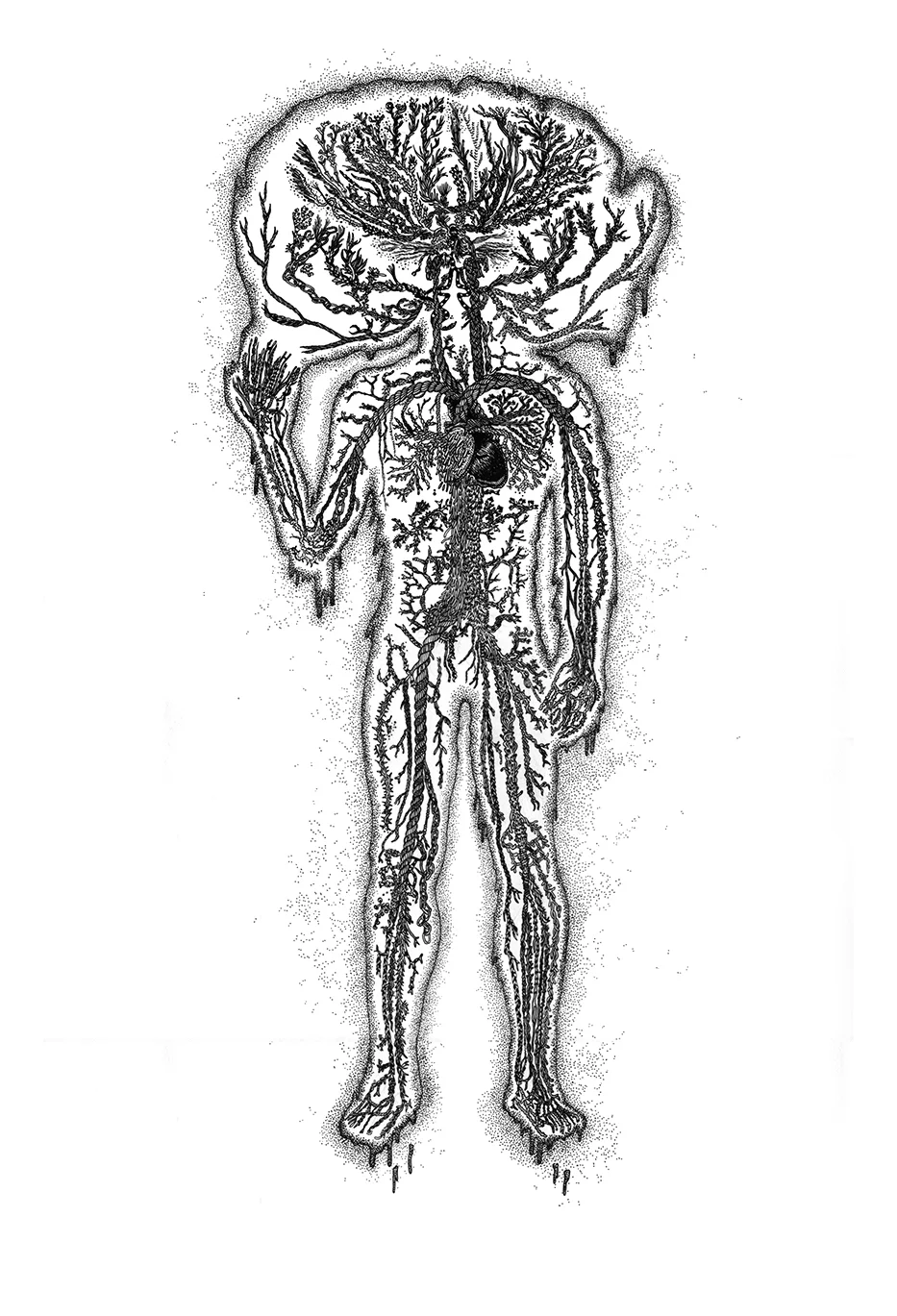

HS: For your piece L'écorché, will you translate the title to English? What is the significance of the head area being splayed out? It's almost auric.

AdPT: "Écorché" literally means "skinned". It sounds gruesome but this piece is directly inspired by old anatomical drawings given to medical students. The one I used is, if I'm not mistaken, of the nervous system. So what it represents is your entire nervous system spread out, it's an educational tool ;). I've always been fascinated by the intricacy, delicacy and slight gruesomeness of these scientific plates. I also love the similarities between how our bodies are designed and how plants grow so when I saw these original drawings, I couldn't help but think about plants and ropes and how we all swarm and shimmer like the nature that surrounds us. I enjoyed mixing scientific codes and almost mystical imagery for this drawing.

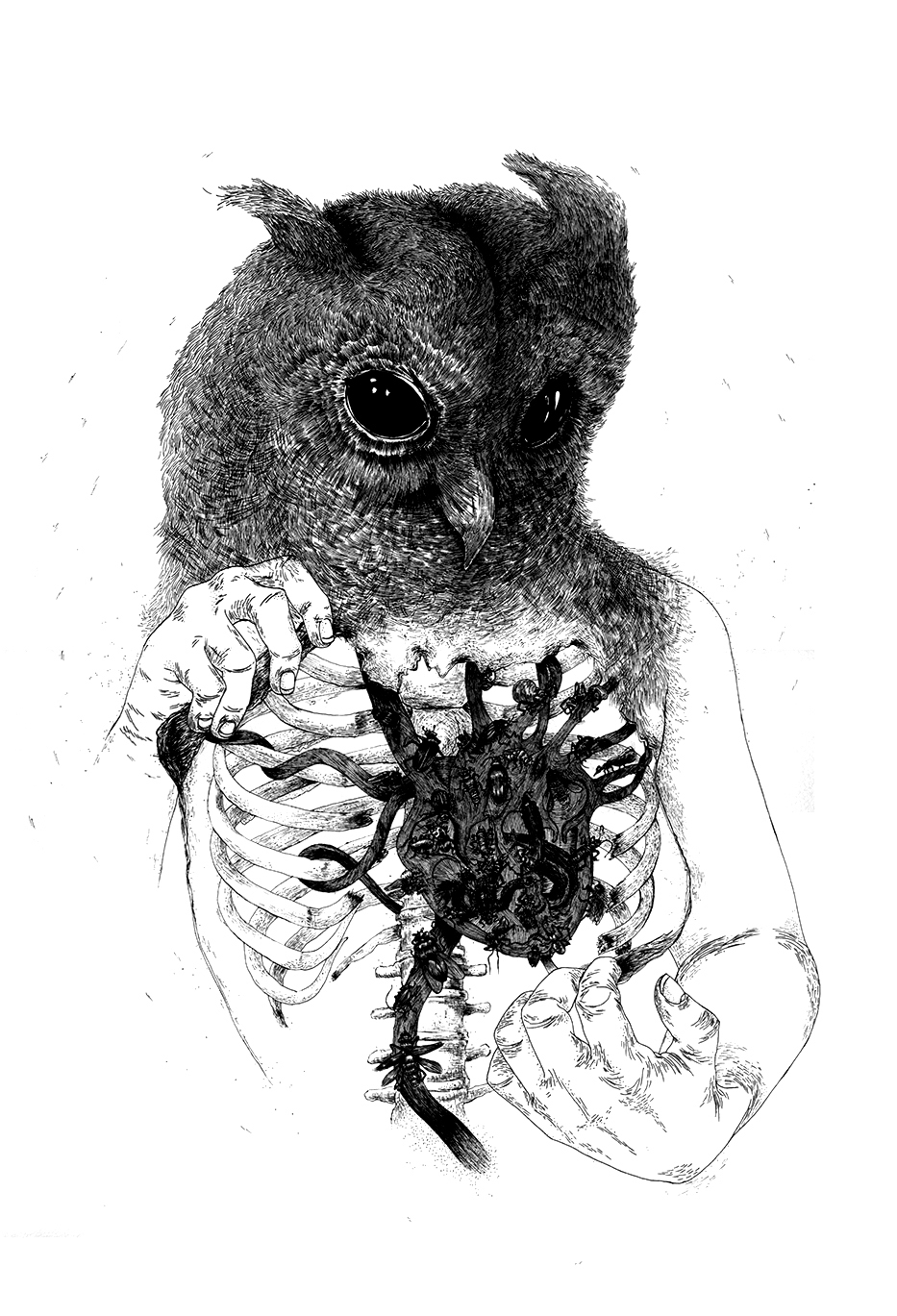

AdPT: Chimère really started with a sketch of an open heart and all the insects crawling in it. I then had this idea of showing it. In French "a coeur ouvert" means "open heart" and means you're revealing yourself. And as for the owl, it's just a magical and majestic nocturnal animal that seemed to fit well!

AdPT: Ouroboros is directly inspired by the old school Christian "vanities" that people had in their houses to reflect on what was truly important in life. I wanted to play with the symbols and really exaggerate the imagery. Make it almost cartoonish. And I loved incorporating all these tiny details. It's a way of creating a story inside the drawing.

AdPT: Nature Morte came to me as a weird and creepy "vision" of eyes really peering at you through these fragile yet intense flowers. The medallion shape is a very traditional shape you find in a lot of classic paintings. So again, it's my way of playing with very traditional classic codes.