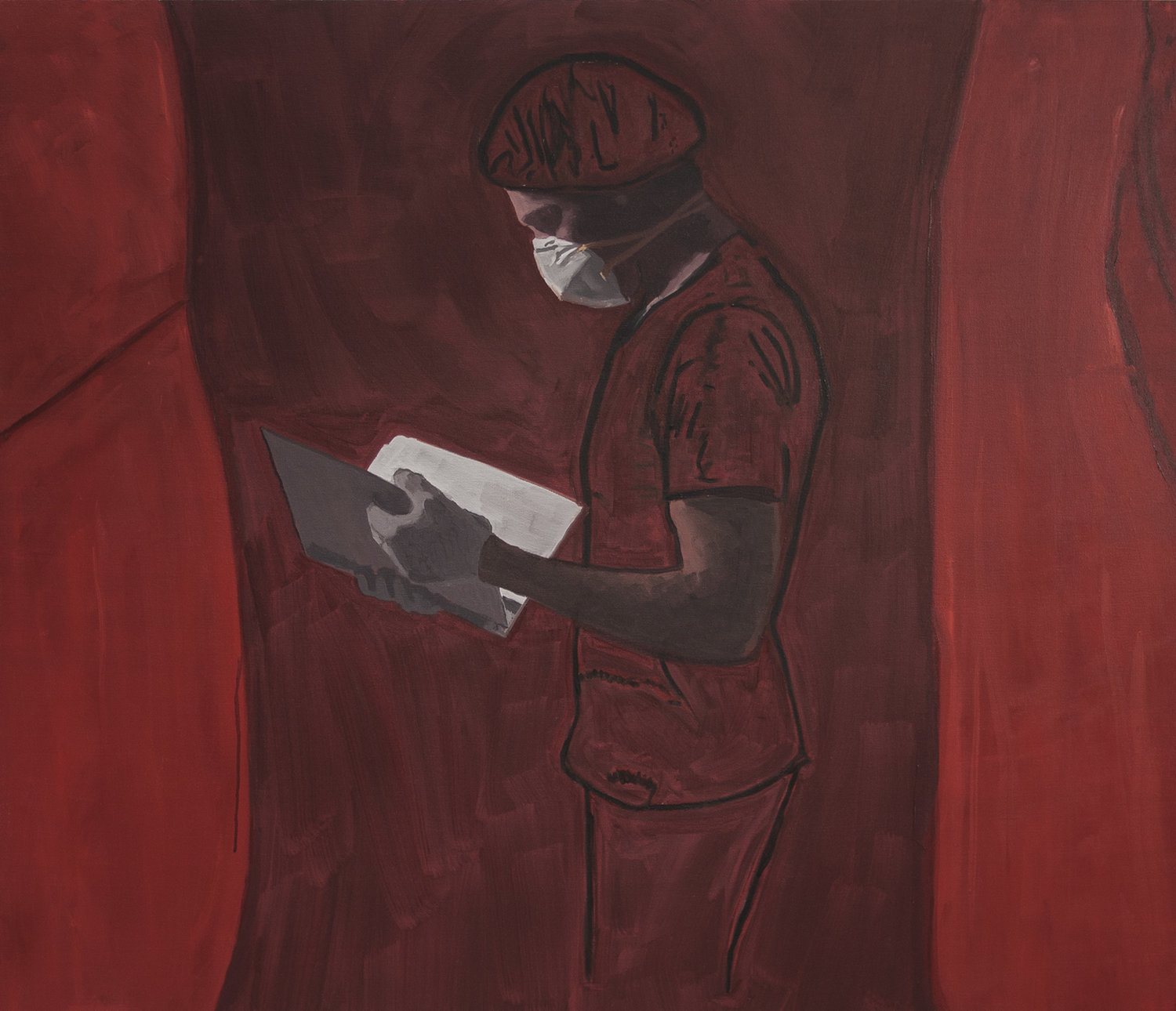

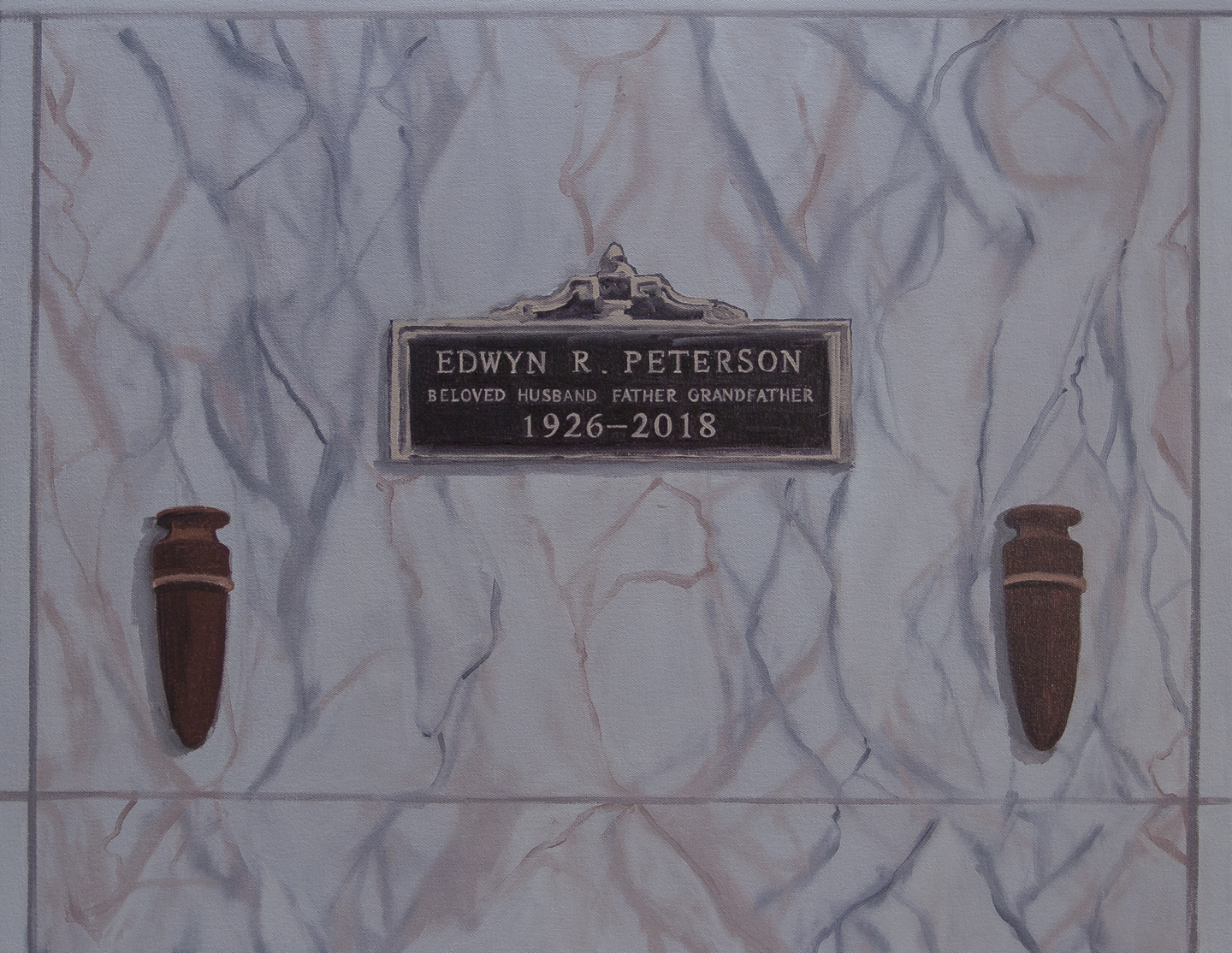

“In Lieu of Flowers” — Paintings Questioning Western Mourning Customs by Patrick Morris

When Patrick Morris’s parents were diagnosed with terminal illnesses, he was forced to navigate the flawed mourning customs we have in the West. Instead of avoiding the grief and existential weight of death, he explored his experiences in his paintings.

HS: When did you start to incorporate death themes into your art and why?

PM: I started working on this series, In Lieu of Flowers, about a year and a half ago, when my dad was first diagnosed with a fatal disease.

About four years earlier, my Mom had died. She died from complications due to cancer, only three weeks from when she was first hospitalized for stomach pain.

In the midst of losing my second parent, I decided to confront death with my paintings. Death makes one feel so powerless, but I chose to explore that rather than push it away.

HS: Does contemplating death comfort or unsettle you?

PM: It’s healthy to contemplate death. Thinking about death can totally be unsettling, which is why most people avoid it their whole life. But then they have regrets. The best we can do is to be open to it, to ask questions, and to accept what is unknown. It may sound strange, but the more I open up to death, the more I feel at peace with death.

HS: Are you making this work to work on your relationship with death, or is it social commentary on grieving customs— or something else entirely?

PM: I do both. In Lieu of Flowers dealt with my parents’ mortalities. But I’m also critiquing the American funeral industry in my paintings. Obviously, the funeral industry preys on vulnerable people when they’re in need. It’s greedy, it’s dishonest, and it needs to change. I believe it will.*

While exploring that aspect of death, I learned about new rituals and new possibilities for the disposal of human remains. Some examples are green burial and the Urban Death Project.

HS: What intrigues you about mourning customs?

PM: My parents both opted for open caskets, which I find problematic— the toxic chemicals, embalming tools such as the trocar, sewing the jaw shut, spooky cosmetics… My wife is from Norway, and it’s interesting to see her reaction to the American traditions. In Norway, embalming is pretty much non-existent. Nevertheless, the undertaker will let you see the body of your family member if you want to. They keep the body in a cold room.

The body is placed in a wooden casket, and that goes directly into the ground (as opposed to air-tight caskets made of steel, or expensive cement vaulting). Another difference is the sheer beauty of the cemeteries in Norway.

Fresh flowers are regularly maintained by family members, and around Christmas-time, many families put lit candles in front of the headstones. It's more civilized than draining blood, more respectful than vacuuming out the intestines, and more environmentally responsible than poisoning the earth with Formaldehyde.

HS: Is there something you are trying to convey to your audience through your paintings?

PM: The paintings are just as much about paint as they are about content, which has recently been on death. I love mixing colors and the abstract qualities of paint. If people appreciate the layering and the brush strokes, that makes me happy. I also like when people come up with stories from these paintings. I use specific color combinations. They are supposed to reflect the energy of the subject matter.

HS: Are the people in your paintings significant to you? Are they people you know? Why did you choose their images?

PM: Yes, they are people who I care about. My models have been close friends, fellow artists who I respect, and my two sisters. For this series, I wanted to tap into that knowledge that I’ll miss these people when they die. By creating pseudo-mourning portraits, I could spend more time with those who I care about, and that led to interesting conversations about death.

I love your use of bold color and how the figures are often the only aspect of your paintings that are depicted with realism. Can you discuss your aesthetic choices?

Thank you. Color is the most significant aspect of the medium. What I respond to most while looking at other people's paintings is color. It's exciting when light and hue will capture a certain energy. It has to do with temporary states, the fleeting color combinations that surround us.

I am drawn to the figure and realism. I put that realism next to the flat, simplified, more abstract nature of the art form because I want the viewer to know this is a painting. In Lieu of Flowers has a heavily graphic style, cartoony at times. I wanted to contrast the heavy subject matter with something more playful. I also used more vibrant, bolder color choices in these paintings in order to counter the somber subject matter.

Artist’s Statement for Patrick Morris, “In Lieu of Flowers”

I make paintings out of love for color, and I make paintings because it is by making things that I find meaning. In my paintings, I base colors off of things that are really in my life, like a beautiful pair of shoes or a favorite tablecloth. The act of painting takes patience, is challenging, and is best when it’s playful.

Before I begin a painting, I make drawings, take photos, and create color studies in order to distil my idea. I stage photographs of people who I care about with the intent to use them as references in my work. I trust my instincts when I begin to paint, and I engage with my paintings along the way, almost as though we’re having a conversation.

Throughout my work, I explore color, the figure, and flatness. My recent paintings continue with those themes and introduce the subject of death. Last October, my dad was diagnosed with a fatal disease, Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. I did not know how much longer he would live, and his looming death pervaded my thoughts. ‘In Lieu of Flowers’ hints at a narrative about death and mourning, using a backdrop of domestic customs of death (’Selecting A Casket,’ ‘Embalmer,’ and ’The Eulogy’). I became interested in outmoded mourning customs, such as mourning portraiture and post-mortem photography, in which the deceased were painted and photographed to memorialize the dead. These customs held significance for the bereaved at that time, but from another generation’s perspective, it feels unsettling and alien. These same observations can be applied to our current customs such as embalming, the open casket, and interment in extravagant, ‘cutting edge’ cemeteries.

I am a painter in Los Angeles, California and I got my BFA in Painting/Drawing from California College of the Arts.

Instagram: @patrickmuseum

Website: patrickmuseum.com

*There are funeral homes working on taking greed out of the funeral industry. For example, Undertaking LA.