Alzheimer's, the Death of a Relationship— An Interview with Colleen Longo Collins

Colleen Longo Collins loves her grandmother as much as it is possible for one human to love another, and her grandmother loves Colleen unconditionally. Colleen’s grandmother grew up in the French Riviera, in Cannes, moved to Santa Barbara in her early 20s, and made a career for herself in the LA fashion world. Growing up, Colleen took refuge at her grandmother’s house because her mother was creating a career and her father was emotionally unstable. In her grandma, Colleen found a person who was always had time to hear about her life, to paint her nails, to look through closets of clothes from around the world. Her grandma modeled femininity for her, but more importantly modeled love. Without further ado an edited interview with Colleen Longo Collins:

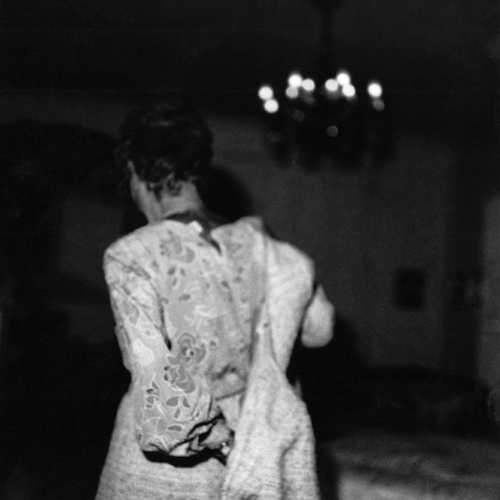

Photos by Colleen Longo Collins @tenaciousnostalgia

CLC: She would pick me up from school in her little two-door, old-school, champagne-colored Mercedes that had sheepskin seat covers. We would listen to soundtracks of the chorus line and she would take me to my favorite restaurant to get a Shirley Temple. There were these very key moments of being with her that really felt like a very loving childhood. It was very far away from the sea saw of what was really going on at home for me. Then in high school, we would make time to see each other because I lived in Alameda and she lives in LA. Either she would fly up or I would fly down. Then when I went to college at Humboldt and I think I change my major five times in my first year of school.

HS: Really? What from?

CLC: When I went into college I was a religious studies major. I took a couple of religion classes and I developed some relationships with the advisors. Then I was like, “No, not really into this.” From there I went into my french major and, oh, my grandmother was so excited because I didn’t take french in high school I took Spanish. High school was just not really about school for me. I was way more interested in social activities than classes.

It was kind of like, “Okay I’m going to do this. I’m going to learn french.” We started developing a weekly chat so she could help me with my homework and she would speak french to me. That was really sweet. That was my sophomore year, and because of the major change I had decided to do a year abroad. I had applied to the program which just so happened to be in Aix-en-Provence which is in the South of France. My mother also did a couple years of college there, so it was really special and sweet to feel like this tradition happening there. Of course, Aix is only about 45 minutes from Cannes so my grandma knew all about it. My junior year I left to move to the South of France.

Interestingly enough, as we’re talking about death, about a month after I left a friend from home died. I was 19 and one of my good guy friends from high school got diagnosed with some awful stomach cancer when he was 17. He went into remission and then it came back. I think the month after I left and was living in France, he passed away. Here I am in this foreign country, don’t speak the language, don’t know anybody, and one of my friends dies from home. I had nobody to mourn with. It was a very dark couple of months for me. I was very depressed and I didn’t want to learn. I was very resistant to learning this language because I just couldn’t get it. It was a very sad time.

That was my first real introduction to building a relationship with death. It took over the year, but I finally had a couple friends visit me, and then I ended up in Ibiza at the end of the following summer. I had two of my girlfriends, Michelle and Katy, that visited me. They were also very close with my friend Chris, who had passed away. We finally had, not a seance, but a meeting. We were all torn up about Chris and we just started to talk about building a relationship with death— what does that mean and what does that look like? That helped to start to process the grieving stages and pull myself out of the darkness. It felt like a tangible way of honoring him. That’s what we did.

Anyway, my grandmother came to visit me in Aix. We had a week together there. We walked around went to Cannes, visited her friends there. It was just really magical. At the time, I remember thinking how special that, “God, I’m nineteen years old and I’m traveling in France with my grandmother.” It was very cool. Then we went to Paris for a week and then she flew back to California and I met up with a friend in Amsterdam. I had spent two weeks with her and it was so special. I’ll never forget that trip.

Then I came back. I had taken a photography class in my second semester of my sophomore year but I was not an art major. However, when I was in France I took some community photography classes as well. When I came back I met with Don, who was my photography teacher from class 1, and he told me, “I think you have a really good eye. I’ll mentor you. You can do direct studies with me.” I was just like okay I’ll become a studio art major. Because I was in France for a year I had enough french classes to have a french minor. I ended up with a studio art major and a french minor.

Then graduation happened and she came out for that. Then I was like, “Okay, I got into grad school. I’m moving to New York.” I moved to New York in 2003 and we just continued to, of course, talk on the phone and see each other on holidays.

In February of 2010, my uncle passed away— my grandmother’s son. He had been struggling with alcoholism for almost two decades. He would be dry for five, six, seven, eight years and then relapse. It was very sad, very awful, saddest for my grandma. I mean she just bent over backward for him, would go to AA meetings with him, pray for him, all of these things. Eventually, it just took him. It wasn’t even like him and I were that close. He would send me a birthday card. I would see him at Christmas. He was very nice but we didn’t have a close relationship by any means. It was a weird point because when he died, I was like, “Okay, I give up on New York.” It was very weird how that influenced my wanting to leave. Again, I wasn’t really close to him. It was just the straw that broke the camels back. I was done.

I had just been in Humboldt for that New Years. I had decided to craft this plan with Paul and Julie Jo, to do WWOOF-ing on their farm. It was very serendipitous. I knew I had to come to California, on multiple levels. I didn’t know if I was really done-done with New York but I knew I wanted a year break. I moved back in September 2010 and lived on the farm for a little over six months. Then Britta and I shacked up together and moved into Westhaven.

Right around then is when I started to see things were off with my grandmother. I can’t remember if there was a phone call— I think it was a visit. I had gone down for a visit and I was staying at my grandma’s. While she was trying to find plans for this apartment building that she had, she got so frustrated. All of a sudden, she was angry with me. I remember thinking, “Why is grandma wigging out? What’s going on? I’ve never seen this?” I tried to calm her down, and then like we got into a really silly fight. I just wanted to be a bitch and then she came in kind of crying. Of course, I felt awful. I just remember that interaction being so strange and so out of character. She was still living by herself, still cooking for herself, and still taking care of herself, but I had started to notice a couple of weird things. She was going over to the neighbors to use their microwave when her microwave worked just fine. She was putting toasted toast in a drawer in the kitchen.

When Britta and I had been at the Westhaven house for a year, I arranged with my mom to have her and my grandma come to visit and to see the place. My mom got my grandma up there. At this time we had the first family conversation to say, “Does she want to go talk to somebody?” We were thinking a therapist. That’s when we started to notice everything. She didn’t remember what room she was sleeping in. It was starting to happen. That was probably the end of 2010, beginning of 2011.

That January my mom took my grandma to the doctor who ran a series of questions. She totally failed it. Couldn’t remember what year it was. Couldn’t remember who the president was. I don’t know how it was for my mom, but when I heard all of that— it was really really sad, and that’s when it started.

HS: What was going through your head when you realized that she had Alzheimer’s? Did you understand what would happen?

CLC: I feel like there were two things going on. There was the super-anal-Virgo-get-shit-done-let’s-take-care-of-business mode that took over. “Okay mom, what are we going to do? Do we need to get her on drugs? Do we need to get her brain tester classes or books? Let’s get her a big calendar, so she can see things. Let’s write notes all over the house so she can see things.” I was being very logistical about how to remedy the situation. Then there was like the other little scenario, “That’s it. She’s done. She’s not going to remember who I am.” I felt like slowing down time or like boom it’s done, it’s over.

What actually happens, or happened to us and I’ve read happens to others, is that it’s a very slow process. For the first year, it was all about my mom and I getting her to really understand what was going on. “This is happening. You can’t drive anymore grandma. You can’t. You just can’t drive anymore.”

Label maker everything. Go down, make seven meals for the week, so she could just pull something out and eat it. Then we started to have somebody come from like nine to five three days a week. When we started to have that, that’s when all of these other things started like sprouting up. The first caretaker could never get into the house. Then the second caretaker would always get kicked out. She would be there for awhile and then my grandma would be like, “Okay, goodbye.” So that was the first round of caretakers. It was very part time. Then she started losing a lot of weight. She’s always been svelte, but she got real skinny.

Then there was a shift. There was a lot of resisting because she didn’t know what was going on. Even when you talk to her about it, she would kind of be with youbut then disappear. There started to be a lot more of the stuffing things around the house. We couldn’t find her diamond earrings because she had wadded them up in a kleenex and thrown them away. She would go to the Wells Fargo, pull out like $3000 and then hide the cash in the house, and of course, forget about it.

HS: Is that something that’s normal with Alzheimer’s?

CLC: Absolutely, there is definitely a phase with Alzheimer’s where money goes out the door. They all of a sudden get very generous. Of course, this causes lots of problems. They give people, strangers, anything, everything.

Then you’d open up drawers and there would be the most random shit in there— a coffee mug with coffee in it, in a drawer with sweaters. Very strange, everything was very strange in the house. My mom and I learned very quickly that she was going to need full-time care. Since my mom lives up north, I was up in Humboldt, and she’s down in LA, it wasn’t like we knew anyone who we trusted to start paying. It’s a very difficult process.

There’s this company called Home Instead which became our ally for a while. More and more, they deal with memory care. There are memory care facilities. There are memory care workers. This stands for dementia and Alzheimer’s. We started getting our caretakers from them and we went through about six of them. The first living woman, Cora, did good for what she was— but me, I just felt like the food she was feeding my grandmother was awful, super fatty, super sugary food. She wasn’t specifically trained with Alzheimer’s so I could tell sometimes she would get frustrated, just like anybody would. She would play a little game as though she was angry with my grandma, and I was like, “You can’t do that.” She ended up moving on.

You needed to have a team. You needed to have the person who was there Monday through Friday, and then you had to have the person who comes to support if your weekday person needs time away. Then you need to have a person on the weekend, to relieve the person during the week.

In the first year or two, I started writing about my grandma’s Alzheimer’s, and a lot of it had to do with the return to infancy. That was really the perspective that helped me communicate to myself and to people— the true return to being a baby. You cannot leave a baby alone, we cannot leave her alone. A baby cannot go to the bathroom for itself, you got to change that diaper. You need to feed that baby with your hand. This person might look like an older adult but 100% she is a baby. We pick her up like a baby. We love her like a baby. We hold her like a baby. We feed her like a baby. We put her to bed like a baby. That’s just that’s what it is, 100% that story of the little boy that has the mom…

HS: “Love You Forever,” that’s the book.

CLC: Yeah, it’s totally that.

Then third year, 2013-14, had dramatic changes too. She was able to walk for a long time and feed herself. Then when I would go to visit her, it became about savoring the fact that we could still share a meal together. That’s where I went with it— savoring those little things. It got so quiet around her house.

My mom started going to these support groups in Oakland, in the Bay Area. They had a good one for her. I never actually went with her but she would tell me all about it afterward. There were a few things that would always come up. One was the money thing, how expensive it is to actually take care of somebody. Say this happens to somebody in your immediate family. Say it happens to your mom or your dad or your grandma or your grandpa, or whatever. A lot of people will say if they’re married, “Oh the spouse is going to take care of them,” or, “The daughter is going to take care of them.” It’s obscene to think that. Even though you’re mother took care of you when you were a baby, it’s so different for us as adults doing our life to then take care of this person because it is a round the clock job. It’s not like you can fit in other things because you can’t get a babysitter. It’s so interesting, the caretaking aspects of it. Luckily my grandma had done a really good job of saving her money and lives a very low overhead lifestyle, so we are able to afford this round the clock care for her. It’s around $300 a day, around $100,000 a year, and they say a third of our humanity will have some form of dementia by the year 2060. That’s crazy.

Okay, let’s back up now. My grandmother ate food from farmers markets her whole life. My grandmother walked two miles every morning. She would meet her girlfriends to swim in the pool at 5 p.m. for a half hour. She was on the board of her homeowner's association. She was on the board of her emeritus college school for senior citizens in Santa Monica. She took french political science, Italian, opera, and literature classes from the age of 70 to 83. She read every Shakespeare book multiple times. She played solitaire. She went to plays and shows. She covered the bases. When they say, “Exercise your mind, exercise your body, keep the community, and eat good food,” she did it all. I don’t have an iota of, “God, she should have done more of this or that.” There’s a part of me that thinks in my gut— okay she’s 89 now. When you’re on the planet that long, in my vagina sense way, I think a portion of it might have to do with pollution, might have to do with something toxic in the air or even in the food back in the day. Obviously, we don’t know, but if I was ever going to cast my own cards to say how could she have gotten this… It’s a disease. It’s genetic. It’s whatever it is. They don’t know how you get it. They don’t know how to stop it. I think, “Okay, yes. Definitely eat well balanced leafy green diet, walk, exercise your mind, exercise your body.” She’s done all of that. The only thing I could possibly attribute it to is some pollution-toxic-something in the air that we just can’t avoid and we don’t really know what it is and it’s just there. There are toxins all around us all of the time. When you’re on the planet for this long, those things add up, right?

Or, because we are living in a time where people are living longer than they ever have, maybe it is a very natural thing for the brain to decay. It’s going to start to shut down and go back to the earth. I mean, that’s just the path. Some people get cancer. Some people, I don’t know. Alzheimer’s could also be a very natural way of dying. Starting to slowly shut down. That’s what it is. I cherished sharing a meal together, and now she has to be fed.

Speed it up to last year. I went to Ibiza for a month and I had a lot of angst about leaving for that long. I felt like, “Oh maybe that’s going to happen. Maybe she’s going to die.” I did some deep spirit work about it and decided to really just let it go. Since then I probably have been the most at peace with it.

HS: At peace with death or with Alzheimer’s?

CLC: With her having the Alzheimer’s.

I’ve never had a big fear of death so I don’t feel like I had to work with that. I mean death can be very tragic if it happens to a young person if it happens very spontaneously. When somebody dies in an accident or something like that like it can be shocking because of its abruptness. Then there are deaths where somebody has a disease and you’re hospice-ing them and you know it’s coming. You know it’s coming but it’s coming slowly. I always knew my grandma was going to die, sooner than probably my mom, but it’s more of… Back to my mom’s support group— so one thing was the money, that they all talk about because a lot of people don’t have this extra funds, that’s very traumatizing. The other thing they talk about is that it’s way harder for the immediate family than it even is for the person that has the Alzheimer’s because they’re just slipping away. There was a point where it was very frustrating for her, for sure, but that did not last long. Maybe a year at the most and I would say half a year, in our situation. It’s way harder for the cognitive living family because we’re still 100% taking care of ourselves and we can see the imbalance that’s happening.

I have never seen this amazing support in my mom before. I think my mom has stepped up in ways she didn’t even know that she was capable of. For five years now she has been flying down to LA every two to three weeks to see my grandma for a day or two. My mom calls her every single day and just talks to an ear essentially. She has shown me the capacity of showing up for somebody, that I did not know she was capable. It is really beautiful.

Backing up to before I left for Europe last summer, I had this spiritual session with Kristen Marie. One thing she said to me was, “All the guides and all of the angels are saying that she is completely surrounded by love. She is not alone. She is fully supported and loved and has lived a very full and beautiful life. There are no regrets. It’s all good.” I just remember holding onto that. Now I just see that love every time I see my grandma. She is completely surrounded by love. She has these caretakers that take care of her. She has my mom. She has me. We celebrate her birthday. We send her flowers for every holiday. We’re there for thanksgiving. We’re there for Christmas. She’s not alone. I mean, God, that’s the most beautiful thing we can have at any point in our life and especially at the end of our lives— being surrounded by love, even if you’re a nomad and it’s just one other person just loving you.

HS: How did you handle seeing your grandmother’s progression, and also how did you help comfort your grandmother while she was aware and frustrated?

CLC: To cope I had to see her more often because when I would let too much time pass it was way too traumatic for me. The year I met Chrisray 2012-2013 when we were first dating, I was going down to LA every five weeks or six weeks. That was helpful. When I was there I went into my Virgo mode. I did a lot of organizing, trying to keep things fresh and clean. Getting rid of expired things. Maintaining the home. That was a way I was processing and a way that I was still connecting to her— looking at her books, touching her clothes, folding her sweaters, organizing her secretaries desk, and noticing, “Oh, that’s the way she would write.” I would look at how she used to write.

When I would feel my emotions coming on, I would just write. I have a very long google doc that I would date and then do stream of consciousness writing. I would write down things like, “She can’t really talk, so this is how she talks now. This is what she’s says and this is how it sounds. This is how she was pacing around today.” Just writing about the Alzheimer’s, and that’s where that infancy thing would just keep coming up over and over again.

To comfort her I just tried to not break down, get super sappy and teary-eyed, in front of her. There were times when I would just be so overwhelmed with emotions that I would have to move my face away and just let the tears come, then bring it back and smile. Sometimes through the smiling I would be tearing because it’s a combination of loving somebody so much and knowing that all I’m doing is just being present, sitting next to her and watching her Judge Judy or watching her stare off into the unknown. There’s a lot of that. There’s a lot of staring into the nothingness for them.

The team that she has now is above and beyond amazing. I don’t know how they do it. They are gifted. They are special. They know how to deal with her. Not only to not get frustrated but to like raise the quality of life for her. That’s another thing they talked about in the Alzheimer’s support groups (and things that I have read, and podcasts that I have listened to) the minute that you take them out of their home and they go into a memory care facility or an aging home, across the board the decline is like whoosh, very steep decline. We knew that we were going to keep her in her home until the end. Now the doctors say the only reason she is alive is because of the care that she’s being given.

Danielle’s grandmother, her dad’s mom, died of complications of dementia. One of the things that I’ve read and seen happen, is people with dementia get a lot of UTIs. My grandma does. I remember Danielle telling me that her grandma got a UTI that went unnoticed. That bacterial infection was the thing that took her down.

Different ways you can actually die from Alzheimer’s:

- Not eating because they forget how to eat. They don’t know how to chew or swallow.

- Forgetting to breathe, which is crazy to think about.

- A small infection that goes unnoticed and then breaks down their immune system.

Before the Alzheimer’s she was one of my muses. I’ve been heavily photographing her for about ten years. Another interesting dynamic to our relationship is that she modeled when she was young. She was in this kind of luxurious industry and then here’s her granddaughter that’s a photographer who starts to use her as a muse. I feel like the photographs of her are so elegant and so timeless. Then it just kind of stops.

I did photograph her a couple times with a Holga. I developed that film, and looked at what I wanted to get out of those photos. It was just so interesting. It was just like boom boom boom. There was no need to take more pictures— loss, confusion, loss of identity, frustration. It was all there just in one photoshoot. I still have some Holga’s down there. I still have some film down there and every time I go down I say, “Oh I’m going to photograph my grandmother.” I’ll take pictures with my phone but these past two years I haven’t really shot her with film. I kind of feel like I don’t need to. I think if I hear she has to go to hospice, or I hear that it’s really declining, I’m going to do end of life photos of her. I don’t want to heavily produce work of her current state probably because it’s just too sad for me. I’ve known her to be such a beautiful elegant woman. So many of my photographs display an old beautiful woman. I already have the images I need to document her fragility, the shift, and the change. This is a big change in our relationship. Every time we got together I would photograph her and I don’t do that anymore.

I also had to process the relationship that she now has with the caretakers. It is very intimate and strong. I don’t know if anger or frustration are the right words, but it really annoyed me. There were times in the past year where in my head, I would think, “Can you fucking leave? so I can have time with my grandma, can you not sit right here?” Of course, I would never say this. These were involuntary thoughts, “I want to be with my grandma. I don’t want you here.” That is the young little girl in my being overprotective and traumatized by the situation. The adult in me is like, “Oh my god, I’m so thankful that you are here. I have so much gratitude for the way you love my grandmother and take care of her.” So that’s kind of a mind-fuck.

I would talk about it with my mom after each visit.

It becomes all about now, the present moment. Everything is about, “Oh it’s sunny and we’re together. That’s amazing, and that’s enough.” Also, my own philosophy of the slow passing of time it's something that I talk about and use in my work. I feel that when I’m really present time slows and yet time goes by so fast sometimes. It’s sun and moon, light and dark, young and old, yin and yang. It’s just two sides of the same coin all of the time, back and forth, back and forth.

The whole thing with the Alzheimer’s is nobody has any idea what it is like like unless you have somebody in your life going through it. Seth Rogan’s wife’s mom had it. I don’t know if she’s still alive now. He did this amazing speech in front of a senate hearing on Alzheimer’s research. I just remember hearing it at the time and it just hit the nail on the head about every point. It was like, “Yep, yep, yep, yep, yep. That’s it. That’s it. That’s it.”

I’ve heard some interesting podcasts of people who’ve had Alzheimer’s. This woman who had Alzheimer’s was in was so early along that she was able to document her transition, which was really interesting to hear about. She was younger, so it was different. I can’t imagine when it happens to people who are younger than you would expect. I think my grandma was like eighty-four when it started onsetting. Diane, who is a friend of the Tika community, her husband has early onset Alzheimer’s. I’m just like, “Oh my god.” That’s so young. My grandma lived a full life. She’s not being robbed of anything. I don’t feel like, “Oh god, she didn’t do all the things she wanted to do.” She saw her grandchildren graduate college. She saw me get married. She definitely had Alzheimer’s then but she was able to show up for the civil ceremony in LA, which was really special. I couldn’t have asked for anything more.

HS: In your experience what’s the difference between preparing for death than in preparing for dementia? As a society, we have such a taboo about talking about death, so it’s very shocking to the system when either an accident or a diagnosis happens. Is it similar with Alzheimer’s? Do you feel like there’s something that society could have more awareness of that would make Alzheimer’s less intense?

CLC: The weight of end of life care a hundred and million percent needs to be talked about more. I just can’t say it enough, everyone needs to have a health directive. There are some great podcasts that I’ve been listening to about this. Health directive, do it. Get it done. It saves millions of dollars. It saves families hundreds of thousands of dollars. Most of health care is used in the last third of your life and even more so in the last 10% of your life. I think it is atrocious the amount of money that we spend at the very very end of a life to try to keep that life around in that form and state. I think that is disgusting, in my personal opinion. I’m watching my grandmother go through this. I can say now, “If this happens, euthanasia. If this happens, resuscitate, don’t resuscitate. If I cannot walk for myself, go to the bathroom for myself, feed myself or talk, this is what I want to happen.” Just go through the typical form that they have maybe for the first time when you’re around 35 and then once every 10 years. Check in with yourself, your family, your immediate loved ones, and your close friends to be like, “Okay I used to think this but now I’ve updated it to this.” I can’t express that enough. Especially for the child-parent relationship— once your parents hit 65, talk to them. Ask them what do they want to be done. Do they want to be cremated? Do they want to be buried? Where do they want to be buried? How? Do they want to be in a coffin? Do they want to be in an urn? Those sorts of conversations, huge.

I’ve been very clear with my mom that I want to be there when my grandmother passes. If she doesn’t pass in her sleep, if there is an inkling, if hospice is there, she has an NDR but if we were going to pull the plug, I’ve been very clear about wanting to be there.

Preparing for death is a little bit foolish in my perspective because I kind of just feel like preparing for death is preparing for life. It is do or die. You work on your life to be loving, expansive, peaceful, whatever it means to you to be living a fulfilling life, and to me, that is preparing for death. It’s not a different preparation. Yes, there are the logistics. Get your affairs in order. Make it, hopefully, very easy for the next of kin to deal with whatever finances or paperwork or insurance or doling out of money or savings and bonds and stocks. Hopefully, make that very easy for whoever you leave things too. It’s very difficult when there are multiple children involved. I can definitely say that. When there are lots of siblings, I’ve only seen more and more trauma develop because of that. Everything comes up, “Mom didn’t give me that toy when I was at Christmas in 1985 but she gave you that bike.” All that shit destroys families. I’ve seen it happen in my own family and I’ve seen it happen in the families of my friends. It’s very easy if you’re an only child.

I think in preparing for dementia would just be to simplify all the logistical things. Do you live in a one story home? How easy is it to get into that home? What are the locks and the keys and who has those keys? All those simple logistical things. Is the refrigerator working? Do the washer and dryer need to be replaced? Is there a leaky faucet? Simplify all of those things because really what remains, for example in my grandma’s situation right now, is keeping a clean house, making sure the garbage is taken out, making sure there’s food in the fridge, making sure the lights work, the heat works, the air conditioner work. All those really simple things. My grandma doesn’t shop. She’s not a consumer. We consume for her. We get her things we think are nice because it makes it nice for us when we go to visit. We try to keep her home the same, even though it’s all subconscious at this point. Just keeping up with keeping up the house is a big thing if you are somebody that starts to come down with dementia. If you don’t have family or friends or people that check in on you, it can get so scary, so fast. Literally not knowing where to go to the bathroom so you just poop all over the place. The body and the functions and the humanness and the cleanliness— the more sound mind you have the more likely you are to keep a clean home. If you have instability, if you have like issues, then your home starts to show it. It’s scary to think about people who don’t have the support. That to me is one of the saddest things that could happen.

HS: What are the options for someone who doesn’t have money. Do you know?

CLC: Medicare and Medicaid. There is a portion of money that is federally funded that will provide up to a certain amount of home care. It’s not enough, though. Then you get put in one of those homes. You’re just left there. I’ve walked by these homes. I’ve peered in. It’s not good. It’s very sad and it’s very lonely. It just goes back to like the simple things.

When I say you need a partner, I don’t mean like a lover-partner. You just need somebody that cares about you. Sometimes this person could be somebody you didn’t know at all in your life but all of a sudden has an affinity toward taking an interest in you, checking in on you, and being around for you. I mean really just that. The biggest blessing is if you have someone who is interested in your well-being— who will bring you food, make sure your garbage got taken out, bring you a blanket if you’re cold, turn on the AC if it’s hot. It all gets so simple. Nothing else matters.

Every time I go down there and I’m like, “Ugh conventional chicken and fuckin' Lucerne milk.” I’m scoffing at the refrigerator and I’m wondering, “Why can’t we get her organic stuff?” My mom is like, “I hate to say it honey, but that’s low on the totem pole right now.” It’s so true, but to me, this young 30 something, organic is where I go because that’s what I’m working on in my life. Or the recycling, “You guys aren’t recycling. Why can’t you recycle?! Why are you putting it all in the same basket? Stop buying bottled water get a water filter.” This is because I’m living in the present where I’m trying to make the world a better place or our lives better. I don’t want to say that at the end of the day it doesn’t matter, but when you’re dealing with somebody who’s days are numbered, those things kind of don’t matter. It also reminds me of how much really isn’t being done. The caretakers are doing excellent at taking care of my grandmother but if they’re not recycling, can you imagine what an entire memory care facility is doing? It’s insane.

HS: How do you think this experience has changed you?

CLC: Well, I feel very blessed to have insight on this. It feels like I’ve peered into something, peeled up the carpet, looked behind the curtain. It’s a different dimension in a way. People talk about Alzheimer’s like, “She forgot her keys. She’s getting early onset.” People say silly things in relation to Alzheimer's and I’m just like, “No, no, no, no, no.”

A lot of it has to do with how close I am to my grandmother. If it’s somebody in your life that you’re super close too, a super close loved one, it makes you love them so much more. It makes you be thankful for all the time and wonderful memories you did have. I feel like I did a pretty good job of asking her to tell me stories about the old country, her life when she was growing up, but sometimes I wish she was all with it right now so I could ask even more questions, hear even more stories. When I was leaving New York I met this girl who worked next door to me her grandma had Alzheimer’s. She said something about videoing her grandmother. I wish I had done more video with my grandma before the Alzheimer’s. That’s something that I kind of put out there to people now. My mom doesn’t really like pictures taken of her, nor does she really like videos of her, but I can definitely sense that I will be videoing her more in the next 10 years. Video is a beautiful way of remembering somebody.

This is the other thing that happens. The longer the Alzheimer’s is with you, is in your family, you’re around it, the more those current memories start to become stronger than the older memories of when she was bopping around the house, cooking Thanksgiving dinner, shopping, getting in and out of the car, and driving. Another thing I do when I go down there is I look at the old pictures to remember, to get in touch with her vitality and how voluptuous she was, her skin, her hair. I’m trying to keep that essence of her in the orbit right next to her current state of being. I’m so tuned into like when people start to die when people start to go. The color of their skin gets drab. Their hair turns all white. Their life is draining out and you can see it. It’s like looking at a tree, knowing that you’re staring at the leaves and you can’t see it growing right in front of your face but you know that it’s growing right in front of your face. That’s how I see my grandma. I’m looking at her and I’m not looking at the time-lapse but I know the time-lapse is happening.

HS: How has your relationship with her death changed? How do you feel about her physically dying?

CLC: Great. I feel like it will be a blessing. I’m prepared and ready for it. I just want to be there and witness and hold space. That’s it. That’s all there is to do. Again, it’s very simple. It’s not complicated. It’s not gripping. It’s different with an old person. I can’t imagine if it was my baby or my three or four-year-old kid who got a terminal illness. That would be a completely different story, and I would again have to build another relationship with death in order to learn what that transition would teach me. With my grandmother, it’s the end of her life. If anything, I’m mourning my own needs and wants. I’m sad that she can’t talk to me and tell me her stories. I’m sad that she can’t take me shopping. I’m sad that we can’t go out. She can’t get in the car and drive me to dinner. I’m sad that I can’t show her my home in San Francisco. It’s all "me" stuff. It’s all ego. It’s all personal gain, personal desires. Not that any of that is bad. It’s all good love, but the amount of gratitude and love and time that we’ve had far outweigh those things I wish I could still do with her.

HS: If there’s one thing, one or two things, that you wish you could share with people that you’ve got from this experience. What would those things be?

CLC: The photographer in me immediately says document. Document your loved ones. Take pictures, mundane pictures, festive pictures, pictures when you visit them. Even if it’s just a small little selfie or snap. But that’s me.

Meet them where they’re at now and find out what their wishes are. Even if the first or second or third time, they say they don’t want to talk about it, they don’t want to think about it, just keep asking. It can just save so much money. Not that it’s about saving money but it’s also not about just throwing money at the situation to put a band-aid over it. Find out what their wishes are and do your best to uphold them. My mom did get the word that my grandma wanted to stay in her home, so we’re making that happen for her. She gets to stay in her home.

Simplify all of it— from the clothes, to what’s in the bathroom, to what's in the kitchen, to how the bills are paid, how the money comes in. Make it simple so that if Alzheimer’s does happen, whoever is next of kin won’t have the stress of figuring it out. It’s going to be stressful enough to deal with the transition of somebody getting dementia and Alzheimer’s.

There’s a part of us living-working-humans, when we’re very young and vital and active (and that’s for most of our lives), that needs to do. I cannot show up to my grandma’s house and not do anything and my mom’s the same way. We’re doers. You want to make sure everything works. You want to sweep. You want to clean. You want to get her blanket. She’s just fuckin’ sitting in a chair not doing anything. There have definitely been spiritual moments where I’m like, “Wow, here is the art of doing nothing.” [laughs] Who knows what’s going on in her head. Nothing really. I don’t know.

HS: Is there anything else that you want to say?

CLC: The phases are crazy from going through like the denial of, “Okay she’s going to beat this,” to the severity of, “Oh my god, it’s all or nothing.” Going from thinking she is immediately not going to be able to talk, not going to be able to walk, not going to be able to eat— to then the personal suffering. When you deal with Alzheimer’s, it becomes about the people left behind. It’s about the people that are still cognitive and aware and present, communicating, experiencing life, and talking about ideas. Not being able to do that with her is what’s hard. That’s where your personal journey takes over. That’s what happened for me. It’s a personal journey of letting go, honoring what was, what is, what will be. There’s nothing to clench onto or grip toward. There’s is definitely a sense of helplessness but it’s a different helplessness. It’s like you can’t do anything about the situation but that’s okay you don’t have to do anything about the situation. Are you okay with not doing anything about the situation? If you’re not, then that’s what you have to work on.

There is also the very natural, genuine sadness of missing her being interested in my life— asking me questions about Chrisray, asking me questions about our house. That’s the whole thing, though, I’m missing her and she’s not even dead. That is a very real thing that I talk about with my mom. I miss her. I’ve already missed her in the past couple of years as if she’s gone. Now when I see her it’s a little icing on the cake, a little treat. Now it’s like I can still hug her and giver her a kiss. How sweet. I awe. That feels like an added little gift from the universe because we can’t communicate about what’s happening in life. She’s not the woman, the grandma, the caretaker, the guardian that she used to be for me.

The end is near for her, and it is not for me. I just sit with that and I contemplate what that means because that is definitely a concept that spans a lot of other scenarios. Everybody is somewhere different on their little path.

I can’t say that this experience has put me in a state where I’m going to live in the present moment, that it’s taught me all of that. I had already had that going on in my life, from the first experience of death I had.

I remember, when she still had a little bit of her wits, going on a drive with her and she was in the passenger seat. I got really emotional. My voice was cracking. I grabbed her hand and I just said, “Grandma I want to ask you to make sure that you will be my guardian angel, that you’ll look out for me and that you’ll always be there. I’m just saying it even though I know you’re going to say, ‘Of course I will be.’ I’m saying it to the ethers. I’m saying it to the universe. I want you to be always with me.” She said, “Of course, of course, of course.” That went hand in hand with an experience I had soon after.

Not too long after, I went to a meditation retreat and this one guy sang this song at the end, and it was beautiful, beautiful song. The song goes, “May you always remember me loving you.” When the song was happening I was just bawling because it was all about my grandmother and it was her singing it to me— her spirit saying, “May you always remember me loving you.” Without a doubt, the tenderest bit in my heart, inside my being, inside my spirit and soul, knows that when you have love like that in your life, nothing compares. Nothing else matters. How lucky am I to have had this person in my life, that happened to be my maternal grandmother, that happened to teach me and practice unconditional love? Without a doubt, I know what that means. I would never take that for granted. That gave me so much confidence in myself as a being. If you have somebody in your life that just loves you no matter what, no matter if you die your hair crazy colors, who will love you if you have dreadlocks, or if you have tattoos, or if you marry someone outside of your religion, or out of your race, or any of those things, you are so fortunate. That’s what she was for me. A lot of people have that with their mom, or with their dad, or with their siblings, and then a lot of people don’t have that from anybody. That is very sad. That can make life very, very difficult.

HS: Wow, there was a lot of good stuff in our conversation. Not related to Alzheimer’s, I have a question I ask to everyone that I interview: What do you want your funeral to be like?

CLC: There’s a picture that I pulled out of a national geographic it is a really beautiful picture of this Tibetan girl. She’s laying down and she has these a line of like charcoal patties on her body. They all have incense on them and they’re all burning. It’s unclear if she’s dead or if she’s alive and this is a ritual. I have had the vision in dreams, and journeys, and prayers, where I imagine when it is my time I will take a breath in and my whole body will be filled like a balloon. Then when the life is gone, the air poofs. My whole body deflates and a little bit of smoke comes up. I know that can’t physically happen [laughs].

As technology and science move forward, I’m very open to exploring euthanasia. I resonate with that peaceful injection from my loved ones, with my loved ones around— my children, my grandchildren, my partner. If it is that time, as I have specifically written out, I will have a nice healthy dose of morphine and go into the next world.

I want to be cremated. I haven’t figured out where I want my ashes. I would like my immediate family to have some, and then probably, spread the rest out in the waters of Ibiza. I also like the idea of keeping a good urn of ashes so that when if there’s somebody in the family that feels the need to have a ceremony that they could take those ashes at any time. It doesn’t need to be at the anniversary of my death. It doesn’t need to be on my birthday. I want them to have something they can commune with that means something to them, because honestly after I go, it’s the people that I’m leaving behind, that still around that still have memories of me, that I would want to have something sacramental.

I don’t want to be buried in a box in the ground. I also don’t know if cremation is the best thing we should be doing to our environment so I’m open to changes that happen in the next 10, 15, 20 years— plant a tree in my name, move me into the soil. I want whatever is most environmentally friendly and causes the least amount of resistance for my family because they are the ones that are left behind andI want them to feel good about how my body is taken care of.

I don’t know if there will be more than ten people at my grandmother’s funeral. When you get old, there are not that many people left around. It’s not like when you die young and there are tons of people. It’s such a different type of death. I kind of want to say, “Funerals are for the young.” Then there are all the people that die that don’t have anybody. That’s something I’ve thought about when somebody died and nobody goes to their funeral. I’m sure there’s a group where you could show up to strangers funerals. I like that idea. I’ve thought about that a couple times. Maybe I’ll start doing that occasionally. I’ll go to some strangers funeral that doesn’t have anybody to just be like, “You were loved. You were remembered. You’re not alone.”

There’s this moment that I’ve heard of and read about, where there’s struggle, or not a struggle but a resistance, knowing that death is about to happen. You take their hand and you tell them, “It’s okay. Go ahead,” and then they can go. I’ve heard of this happening a few times, with Danielle’s grandma, my great grandma, and my grandpa. I see that with my grandma, “You’re okay. You can go.” I can’t imagine, even if you’re like out of your mind or diseased or whatever, that struggle to just release into it. I will be there for my grandma to tell her that she can go and that it’s okay.

Colleen Longo Collins is a dear friend, an amazing fine art photographer, and a professional organizer. To see photographs of her grandmother, click HERE. Please follow her photography on Instagram @tenaciousnostalgia.